La Yunta, « Le joug » (c’est-à-dire la pièce de bois permettant d’atteler une paire de bœufs pour la charrue), a été jouée pour la première fois le 29 mai 1971 dans la communauté paysanne de Ahuac, un district rural à 10-15 kilomètres de la ville de Huancayo.

Víctor Zavala Cataño y place les personnages suivants : un jeune paysan, une jeune paysanne, Tío [=oncle] Juan, un négociant, un contremaître, un policier, un juge. Il y a également des voix qui interviennent.

L’action se déroule dans la sierra, c’est-à-dire sur les hauts-plateaux péruviens. La pièce dure plus d’une heure.

Elle commence avec le jeune paysan et le jeune paysanne qui se chamaillent ; le premier poursuit la seconde, dans un jeu de jeunes mariés.

Cependant, elle est soucieuse et mécontente, ce qu’elle exprime en se moquant ardemment de lui qui pense réussir avec ses deux jeunes bœufs afin d’utiliser un joug pour être en mesure de labourer les champs de la communauté.

Le temps qu’il accorde ce projet l’exaspère ; l’omniprésence des bœufs dans la vie de son mari la dérange profondément.

Le jeune paysan va ensuite voir Tío [=oncle] Juan, pour qu’il l’aide à mettre pour la première fois le joug aux bœufs.

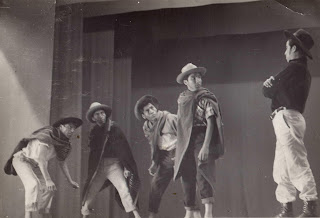

Ils y parviennent et s’ensuit une danse, où deux danseurs ont une veste noire pour l’un, une veste blanche pour l’autre, afin de représenter les deux bœufs.

Suivent un chant du jeune paysan et un autre de la jeune paysanne. Mais la terre est sèche, elle est dure et la pluie ne vient pas.

Que vont également manger les bœufs si rien ne pousse ?

Arrive alors un négociant, qui tient un monologue.

NÉGOCIANT. Je suis négociant en bétail. Je fais commerce de vaches, je fais commerce de taureaux. J’achète les animaux, je les emmène à la ville.

À l’abattoir, je les vends. C’est une bonne affaire.

Bien sûr, cela a ses problèmes, ses petits maux de tête ; mais j’en sors toujours gagnant.

En ville, tout le monde mange de la viande ; pour un petit kilo ils se disputent, pour un petit os ils se griffent.

C’est moi qui leur donne la viande, c’est moi qui leur donne l’os. Mes poches s’engraissent avec la mort des vaches, avec la mort des taureaux.

Quand les vaches manquent, les ânes font l’affaire, les chevaux aussi.(Rit.)

Je suis ami des propriétaires terriens, je suis collègue des autorités, je suis intime des voleurs de bétail.

Je suis d’accord avec leurs principes. Eux aussi prennent leur part, mais les animaux donnent pour tout le monde.

Du cuir sort le fouet. (Il rit.)

J’ai vu de bons taureaux dans cet endroit. Je viens pour les acheter. C’est un bon moment pour le commerce : il n’y a pas d’herbe, il n’y a pas d’eau.

Tous les paysans vendent leurs animaux avant qu’ils ne meurent de faim.

Ils me demandent, s’il vous plaît, d’acheter leurs taureaux, d’acheter leurs vaches.

Moi, je marchande. C’est une mauvaise saison, je dis ; tes bêtes sont maigres ; à l’abattoir je vais perdre de l’argent, on va me payer une misère pour la viande ; je vais te donner moins, donc.

Sinon, mieux vaut que je ne t’achète rien. À toi de voir mon petit père, combien tu vas me payer avec justice.

Alors, je leur fais une grande opération avec des chiffres et des lettres, juste pour faire semblant de payer ce qui est juste, et je leur tends les billets ; eux les prennent.

Pendant qu’ils comptent et qu’ils me remercient, j’emmène le bétail. Pour peu d’argent, je prends les animaux.

(Pause.)

Ici, j’ai vu de bons taureaux ; c’est pour ça que je viens. Les propriétaires ne m’ont rien proposé, mais je vais les tenter.

Je ferai comme si je n’avais rien vu, comme si rien ne m’intéressait. Ainsi je pourrai marchander.

Au passage, je dirai que je ne suis pas de bonne humeur. Je vais faire du bruit pour qu’ils me remarquent.

(Il siffle fortement n’importe quel air.)

Le jeune paysan tourne la tête pour regarder le négociant, mais immédiatement, il détourne le regard, comme s’il n’avait rien vu.

Le négociant siffle encore plus fort, les mains dans les poches, il marche lentement de part et d’autre, mais du coin de l’œil, il observe les paysans.

La jeune paysanne s’approche de lui et le négociant joue à l’idiot. Mais le jeune paysan intervient dit qu’il n’a aucun animal à vendre.

Le négociant lui répond que tout le monde a vendu, car il n’y a ni pâturages, ni eau.

Puis, le négociant feint d’être fatigué, demande de l’eau.

La jeune paysanne dit alors au jeune paysan que même si les animaux deviennent familiers comme la famille, ils vont mourir de soif et de faim. Ce n’est pas une situation tenable, il faut les vendre.

Le jeune paysan, néanmoins refuse de s’en séparer.

« Il va pleuvoir, il doit pleuvoir. Mes taureaux, je ne les vends pas.

Pour une bouche étrangère, ils ne serviront pas de viande.

Ce sont mes fils, ce sont mes frères. »

Il y a l’idée d’aller à la hacienda chercher de la nourriture, chose que lui déconseillent la jeune paysanne ainsi que Tío Juan.

Le chemin est long, les taureaux vont se blesser ou tomber malades, le jeune paysan va se faire voler.

Le jeune paysan décide de partir tout de même ; il ne voulait pas dire au revoir à sa femme, par peur de céder.

Finalement, la jeune paysanne parvient à le voir, et lui part quand même.

La scène suivante marque le retour du jeune paysan.

(Entrent le jeune paysan et Tío Juan. Ils marchent lentement jusqu’à se placer face au public.)

JEUNE PAYSAN. Je reviens de l’hacienda. Hier, il me semble encore que je m’en allais. On dirait que rien ne s’est passé.

Comme un éboulement, le temps m’a balayé.

Me voilà de retour. Merci, oncle, de m’avoir ramené, de m’avoir fait revenir sur la terre que j’ai quittée.

TÍO JUAN. Ce n’est rien, fils.

JEUNE PAYSAN. Je reviens sans mon joug. J’ai perdu mes taureaux à l’hacienda. Pour les sauver de la sécheresse, pour ne pas vendre mes animaux, j’y ai été.

Je reviens le visage triste, le dos chargé de souffrances. Je sens des ombres et des couteaux dans ma poitrine.

TÍO JUAN. C’est un coup de la vie que tu as reçu, fils.

Mais tes yeux se sont ouverts. Tu sais maintenant marcher en terre étrangère. Comme le renard, tu sais avancer en te méfiant.

JEUNE PAYSAN. Tu connais ces choses, oncle. C’est ainsi, cela doit être ainsi.

TÍO JUAN. Ne baisse pas la tête. Regarde vers le sommet de la montagne.

Ne laisse pas tes mains s’affaiblir ; empoigne fortement ta confiance.

L’amertume que tu as goûtée, ne la laisse pas monter jusqu’à tes yeux.

JEUNE PAYSAN. J’ai de la colère. À l’intérieur, je sens que je vais éclater.

Là, tout de suite, je voudrais courir et piétiner les mauvaises herbes, attraper des vers, leur ouvrir le ventre, j’en ai envie.

TÍO JUAN. Tu t’emportes. Tu veux seulement fracasser ta tête contre un rocher sourd.

Il vaut mieux attendre. Mieux vaut unir nos forces. Tu vas te soulager maintenant : en parlant, en racontant ta vie à l’hacienda, tu vas décharger ton cœur.

JEUNE PAYSAN. J’aimerais plutôt bouger mes mains. Ma langue, peut-être qu’elle ne me servira pas.

TÍO JUAN. Je vais appeler ta femme. Elle aussi veut savoir, elle veut voir ce qu’est le puits de l’hacienda.

Tu vas enlever tes épines peu à peu. Nous allons t’accueillir, nous allons partager ta douleur.

Je vais aller chercher ta femme.

JEUNE PAYSAN. Oncle… ! (Il va au fond de la scène et s’y arrête, la tête très basse.)

TÍO JUAN. (L’oncle regarde le Jeune Paysan. Il s’approche, lui tape l’épaule.)

Lève les yeux. Ta femme connaît la couleur de ta pensée. Elle attend ta parole.

JEUNE PAYSAN. Je suis parti fâché contre elle. Vendons un taureau, m’a-t-elle dit. En insultant sa bonne intention je suis parti.

TÍO JUAN. N’évoque pas un mauvais moment, fils.

JEUNE PAYSAN. Je n’ai pas écouté sa parole, je n’ai pas reçu sa voix.

Le jeune paysan raconte alors son périple. Un taureau s’est effondré en raison de sa soif, juste avant un cours d’eau ; heureusement le second taureau y est allé et a appelé le premier.

L’arrivée à la hacienda ensuite a été désagréable ; le contremaître a immédiatement prévenu que jamais les deux taureaux ne tiendraient le choc.

Néanmoins, le jeune paysan a accepté les horribles conditions de travail en échange de l’accès au pâturage ; il fut souligné en même temps que la hacienda était riche, car elle s’était approprié tous les cours d’eau, les déviant vers elle.

Les taureaux ont, bien sûr, vite fait de manger le petit pâturage accordé, et le jeune paysan fut obligé d’acheter des rations de plus, en signant à chaque fois un nouveau contrat, sans pouvoir le lire puisqu’il est illettré.

Il dut signer encore pour un endroit où dormir, une couverture, des infusions, de la coca…

Ce qui aboutit bien sûr à la confiscation des taureaux. Lorsqu’il veut porter plainte, le policier joue aux cartes avec le négociant rencontré auparavant…

Quant au juge, à qui le jeune paysan donne son poncho, il est bien entendu de mèche avec le contremaître.

Naturellement, le jeune paysan tente de récupérer les taureaux et de s’enfuir avec ; il se fait rattraper et arrêter. Désormais, il doit travailler, attaché, dans la hacienda.

Une nuit, alors qu’il est emprisonné, le négociant vient le voir, et lui demande le contact de ses chefs. Il reconnaît alors le jeune paysan à qui il avait essayé d’acheter les taureaux, sans succès.

Et il lui confie que sa femme a vendu les terres, afin de pouvoir le sortir de là. Tío Juan a amené l’argent pour payer le grand propriétaire.

Le jeune paysan est bien sûr atterré de la situation, mais Tío Juan lui donne à lui et sa femme ses propres terres.

->Retour au dossier sur Víctor Zavala Cataño

et le théâtre paysan péruvien